Pisupo Lua Afe Corned Beef 2000 Ap Art History

Primary Commodity Content

Abstruse

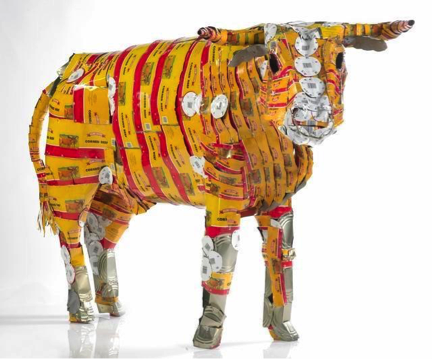

Tuffery, Michael. Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000). 1994. Flattened tin can cans, riveted together. Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa Collection.

Michel Tuffery produced Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000), an entirely metal artwork, in 1994 for an exhibit in Wellington, New Zealand. The piece is one of several metal bulls Tuffery has created; another, Povi Christkeke, Tuffery created to be included in a parade that included Samoan drumming and dancing, a celebration that involved several such bulls moving on wheels downward the streets. Lights and fireworks likewise illuminated the works in a simulated "bullfight" (Hay 2). Both works stand life-size, bulls made completely of crimson and yellow flattened metallic cans. The labels on the cans read "Corned Beefiness" and Tuffery has aligned the silver metal lids to outline the bull'due south face and hooves. The discussion pisupo arose from the initial tinned product brought to New Zealand mid 20th century, pea soup, but the word now specifically implies canned meat. The tinned food is sometimes given as a gift at celebrations (Lythberg 3). Tuffery, a New Zealander of Samoan, European, and Rarotongan beginnings, has worked in the by to synthesize traditional tapa cloths, sculptures or carvings, with contemporary drawings and figuring.

In her writeup for the Christchurch Art Gallery in New Zealand, where Povi Christkeke resides, Jennifer Hay interprets Tuffery'south piece as a "wry socio-political bulletin" concerning the place of foreign imported goods in Samoa as part of the larger presence of colonialism in the Pacific Islands (two). The introduction of canned foods contributed to a change in the diet of Pacific Islanders, and Hay describes a resulting "decline in indigenous cooking skills" (Hay ii). She states that Povi Christkeke also touches on the "touch on of global trade and colonial economic science imposed upon the Pacific Island civilisation and environment" (Hay 2). Hay closely ties dietary and economic changes to a loss of traditional culture. While Hay's interpretation makes the power dynamic articulate, Povi Christkeke is not so explicit. In using the literal cans of beef, Tuffery may be depicting a change in the dietary lifestyle, merely he does not provide united states with answers to what it ways on a cultural level. Tuffery's subtlety propels united states to examine the relationship between the pre-colonial Samoan civilisation and influence of foreign colonialism.

In "Arts of the Contact Zone," Mary Louise Pratt explores what happens when cultures intersect, whether on a linguistic, colonial, or ethnic level. She draws on examples that vary as widely as her son's discovery of the world through baseball cards to a seventeenth-century letter of the alphabet written by an indigenous Andean to King Philip Iii of Spain. Pratt pulls these disparate sources together to define contact zones equally "social spaces where cultures see, disharmonism, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power" (34). Guaman Poma's 1613 alphabetic character, modeled on a typical Spanish "Nueva coronica 'New Relate'" of conquest, delivers, in a European colonial genre, a novel trajectory of the story of the Creation of the earth. Poma seeks to rewrite the history of the Christian world, but with "Andean rather than European peoples at the center of it—Cuzco, not Jerusalem" (Pratt 34). Poma also alternates between Spanish and his native Quechua. Throughout the slice, he replicates, substitutes, reverses, and creates anew. Poma grapples with how colonialism has attempted to define his world, equally he stands at a crossroads of cultures.

Only equally Poma's letter is undeniably a purposeful culmination of components, so likewise are Tuffery'due south bulls. Pisupo Lua Afe and Povi Christkekeare themselves contact zones. Their multi-layered construction forces us to consider their different parts—the physical tins themselves, their spatial arrangement, Povi Christkeke's trip the light fantastic through the parade—in their own right, but also in the narrative of Samoan history. In synthesizing a new form of communication, Poma sought to redefine the order of the colonial world. Pratt discerns that it is not merely the content, simply besides the structure of Poma's letter that enabled him to speak so conspicuously of reconstructing history to include indigenous Andeans. By using the Castilian genre of the chronicle every bit a vehicle for his own original content, Poma comments on what this genre means in itself. Pratt asserts that Poma's letter is autoethnographic, "a text in which people undertake to describe themselves in ways that engage with representations others have made of them" (35). Poma responds to a genre that, up until this point, was a one-manner depiction of the colonized globe past the colonizer. Now he works within this medium itself to button back confronting this colonial characterization, creating a two-way dynamic.

What and then is Tuffery's purpose in arranging his multi-dimensional pieces? Tin can nosotros consider the tin cans of Tuffery'due south bulls as themselves a language, one that began as inexpensive, processed products for consumption? Tuffery uses a well-known object as his 'genre,' but expresses something new. Past using cans of corned beef in the bulls and in the parade, Tuffery is asserting that these foods at present take a place in the realms of bouncy celebration. Is it therefore appropriate to see the canned food as parallel to Poma "using the conqueror's linguistic communication" (Pratt 35)? Past considering the bulls in this light, nosotros imply corned beef in Samoa is representative of some unequal balance of ability because information technology was in a manner indirectly 'forced on' the Samoan people. Earlier we commit to seeing Tuffery's works through Pratt'southward lens, we need to consider what exactly changed with colonization. Applying Pratt'south idea would require distinguishing what authentic elements of Samoan culture exist in their own right, before being subjected to foreign influence. Maybe we need to consider what this line ways before nosotros draw information technology.

Yet how can one trace cultural change if non through the categorization of 'earlier colonialism' and 'after'? In "The Case for Contamination," Kwame Anthony Appiah provides a way of distinguishing change that does not rely on because cultures equally finite, divisional entities. Appiah is wary of the concept of "culture" and, rather than pursue a static set of group characteristics, chooses to examine the decisions individuals make within the group. By thinking of cultures equally "peoples" instead of people, or individuals, we risk engaging in broad judgements about what makes their cultures authentic. Pratt's argument is grounded in language, and she defines authenticity in the differences between Quechua and Spanish, and Andean and European artistic design. Tuffery's work, on the other manus, provides no ways of separating "Samoan culture" from that of foreign influence. His bulls are purposefully a novel synthesis, both literally, in the fused metallic tins, simply also in the way Povi Christkeke moves along with the dancers equally ane mass in the parade.

Peradventure nosotros shouldn't try to pick autonomously Tuffery'due south art, strip by strip. Appiah considers seeking cultural authenticity a fruitless act. Information technology is unrealistic to try to pinpoint ane exact moment with which to ascertain tradition because "trying to notice some primordially authentic culture tin be like peeling an onion" (Appiah vii). Culture is composed of layers of change over time, rather than a consistent uniformity. Moreover, what we think of as traditions—foods, clothing, raw materials—may at one point have really been themselves imported or traded by strange empires. One cannot fit the nuances of a tradition in a box. Trying to ascertain accurate Samoan culture in social club to save information technology from strange products perchance "amounts to telling other people what they ought to value in their ain traditions" (Appiah 7). Thus Samoan "culture" as an abstract concept is incommunicable to ascertain for the purposes of tracing colonial hierarchies and therefore assigning cultural pregnant to new nutrient products. Instead, it is more than fruitful to expect at how individuals respond to change.

Pratt and Appiah's philosophies themselves converge when they consider how individuals create and respond to civilization in the midst of a contact zone. Pratt calls this "transculturation," stating that "while subordinate peoples do not usually control what emanates from the dominant civilisation, they do determine to varying extents what gets absorbed into their ain [civilisation] and what information technology gets used for" (36). Poma actively chose visual elements he incorporated from the European tradition, what Andean spatial symbols to use, and when to speak in Spanish or Quechua to grade a cogent response to Spanish colonialism. Besides, Appiah highlights the bureau an individual has when confronted with cultural deviation. He believes that regarding cultural consumers as passive vessels, or "blank slates on which global commercialism'southward moving finger writes its bulletin . . . is deeply condescending" (Appiah 35). Individuals may use products in means that no longer resemble their original purpose; consumption is an active, non a passive process.

In incorporating corned beef in their diets, Samoans were not blind recipients of foreign colonialism. Health concerns nearly processed nutrient aside, the mere existence of corned beef in Samoa did not immediately or straight cause Samoans to get less "Samoan." Distilling a culture to i label is further rendered impossible when considering individuals' variety of tastes, opinions, and consumer decisions. 1 could argue that introducing this new protein-based ingredient into Samoan cooking offered many individuals more options for preparing satisfying meals. Today, a search on an online recipe collection for "traditional Samoan recipes" yields a range of dishes, from those with corned beefiness and cabbage to others with kokosnoot milk and taro leaves. Clearly, the utilize of corned beef has evolved across its mere novelty as processed meat in a can. Rather than erasing Samoan cooking traditions, corned beefiness has become a part of information technology.

It may seem at first that Appiah fails to account for the power imbalances inherent in colonization, in a manner that Pratt does when she contrasts Quechua and European Castilian, but Appiah is not arguing that settlement and violent change did not occur. Instead he is urging us to distinguish between colonization itself and its meaning for the colonized people on a cultural level. We can consider the cultural implications of foods like corned beefiness from the perspective of what information technology means to Samoans today without evaluating whether fierce change should have occurred at all in the Pacific Islands.

As a living descendant of Samoan ancestry, Tuffery situates himself in gimmicky guild in which individuals decide for themselves how they will comprise corned beef into their lifestyles. Tuffery is not challenging or affirming the food as legitimate, but rather depicting it as a timeline of change. His work and the incorporation of his work in the parade demonstrate a commitment to viewing culture as a dynamic, ever-changing reality. In Pisupo Lua Afe and Povi Christkeke, Tuffery proposes that today, corned beefiness is as much a office of Samoan society equally the drumming and dancing that existed long before it. Ane is not more indicative of "Samoan civilization" than the other—today, the tins are fused to the balderdash in more than just their physical composition. Fine art like Tuffery's bulls helps us understand such contact zones not just in regards to the Pacific Islands, simply in the broader telescopic of colonization and commercialization.

WORKS CITED

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. "The Case for Contamination." The New York Times Magazine, 1 Jan. 2006: n. pag. Spider web. twenty Oct. 2016.

Hay, Jennifer. "Povi Christkeke by Michel Tuffery." Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetu, 15 June 2005: n. pag. Web. 23 October. 2016.

Lythberg, Billie. "Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe." Khan Academy, N.d.: n. pag. Web. 23 October. 2016.

Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts of the Contact Zone." Profession (1991): 33-40. Web.

Tuffery, Michael. Pisupo Lua Afe (Corned Beef 2000). 1994. Flattened tin can cans, riveted together. Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa Collection.

Article Details

How to Cite

Simes, M. (2018). Tin Tin Transmission: Using Corned Beef to Talk About Cultural Change. The Morningside Review, 14. Retrieved from https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/TMR/commodity/view/3466

Source: https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/TMR/article/view/3466

0 Response to "Pisupo Lua Afe Corned Beef 2000 Ap Art History"

Post a Comment